Abstract

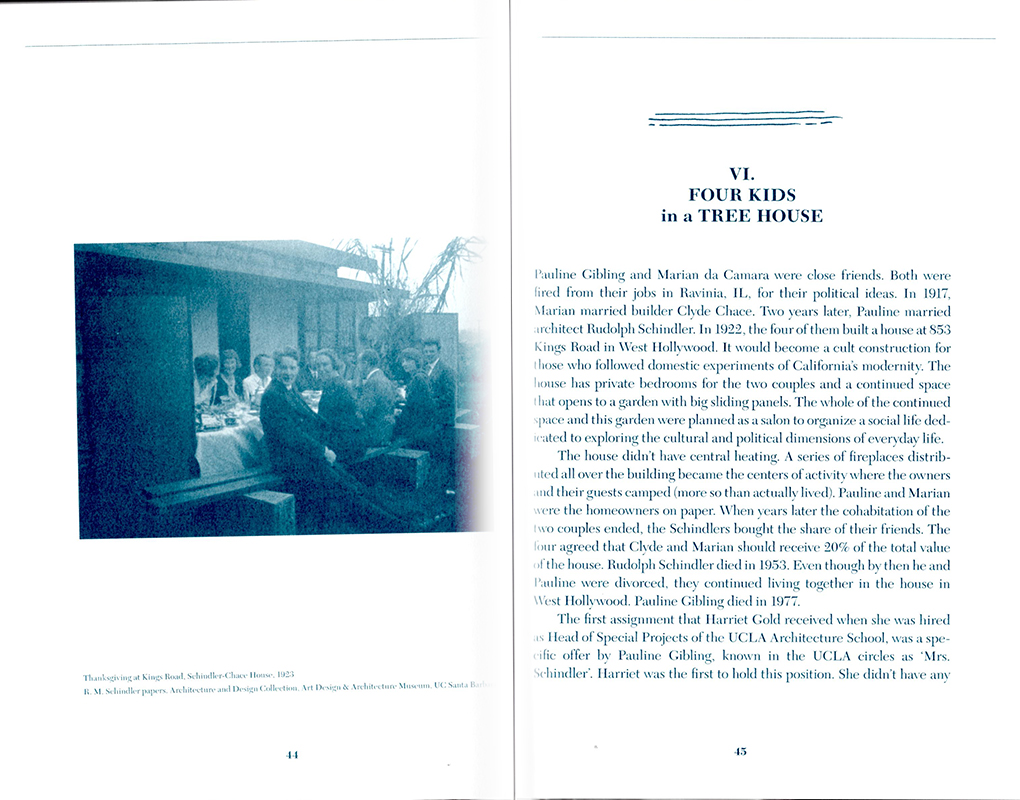

Different Kind of Water Pouring into a Swimming Pool is the book that accompanies the exhibition of the same name that opened on September 20, 2013 in REDCAT. This project by architect Andrés Jaque / Office for Political Innovation problematizes the importance of domestic space and architecture in the construction of the collective. The architect chooses as case studies models that come from California’s garden-city, usually a symbol of disconnection and a recurring metaphor for the height of individuality and comfort.

This publication consists of two parts, first, a compilation of stories that tell the daily life of certain families in California, based on interviews conducted by Andrés Jaque during his many visits to LA. These stories were recorded and are mixed with articles, pictures and histories from other decades to illustrate the everyday architecture of these backyard gardens. The selection of stories is intentionally random and doesn’t respond to any individual preference for a particular case, but rather to the synergy that surrounds them. Far from providing a sociological study, there is an almost literary interest at play in the description of the situations, the shapes of the objects, the atmosphere generated in the spaces and small-scale conversations. These stories occur simultaneously or separated by time and distance, rescuing common problems and situations.

The second part contains a text written and developed by the architect based on various conferences he gave from 2005 to 2013, summarizing his reflections on architecture. In this essay, Jaque forms an open hypothesis in which he compares several examples, disconnected in time, with the aim of understanding how the architecture derived from the experiments of modernity has become embedded in the processes of social construction. To do this, the architect investigates certain historical architectural precedents from their empirical heritage, beyond intentions or preliminary statements, recognizing the forms of citizenship and political interaction that once characterized them.

The relationship between the two parts of this book is defined by the small details that occur in the interior spaces, the attitudes of the characters, and similar ways of solving problems. What other relationship could there be between a textile worker in a small town, a prime example of gartenstadt in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, and a retired, fully contemporary Uruguayan who plants seeds in his garden under the hot California sun?

For Andrés Jaque, it is in these interior spaces in which decisions are made, where the heterogeneity that underlies the garden city is casually discussed, where changes are decided, and the conflicts and negotiations of domestic space are established. These are almost invisible architectures, hidden between palapas and high hedges, conceived from the rhythms of the human body and its daily choreography. Thus, in many of the images that illustrate this publication, the body appears as a key figure that creates a radical contrast. On the one hand, idealized, motionless bodies that have always dictated to us how to live and have defined our living space, as seen in fashion magazines. In this case, it would seem that many modern buildings have been created as effigies of these desired bodies. In contrast to this stasis, Jaque takes stories in which space is defined by the everyday, commonplace need for movement. This is a dynamic architecture, one that is in constant tension, one that prioritizes its performative quality to engage daily transformations and conflicts.

The performative quality to which Jaque refers, both in the exhibition and in this book, is represented symbolically by water—one of the main actors in the Californian backyard gardens. It is not arbitrary that this exhibition take its name from David Hockney’s drawing, “Different Kinds of Waters Pouring into a Swimming Pool, Santa Monica,” 1965, made during his first years in the city. Fascinated by the way people in Los Angeles used water to help shape their private gardens into social spaces, the painting shows a series of simple pipes pouring water into a swimming pool that can’t be seen. Although the material quality of water is elusive, its representation reaches a quasi-architectural dimension, without losing its ephemeral and dynamic aspect. As such, each waterfall becomes an exclusive portrait of a common situation. This might read as a metaphor for the everyday stories that the great narratives of urbanism have left out, but these are certainly places where certain forms of citizenship and interaction, essential to architectural processes occur.

Ruth Estévez